[Content note: Gender, relationships, feminism, manosphere. Quotes, without endorsing and with quite a bit of mocking, mean arguments by terrible people. Some analogical discussion of fatphobia, poorphobia, Islamophobia. This topic is personally enraging to me and I don't promise I can treat it fairly.]

I.

"How dare you compare x to y" it was pretty easy actually

— HRH Misha (@drethelin) August 22, 2014

I recently had a patient, a black guy from the worst part of Detroit, let’s call him Dan, who was telling me of his woes. He came from a really crappy family with a lot of problems, but he was trying really hard to make good. He was working two full-time minimum wage jobs, living off cheap noodles so he could save some money in the bank, trying to scrape a little bit of cash together. Unfortunately, he’d had a breakdown (see: him being in a psychiatric hospital), he was probably going to lose his jobs, and everything was coming tumbling down around him.

And he was getting a little philosophical about it, and he asked – I’m paraphrasing here – why haven’t things worked out for me? I’m hard-working, I’ve never missed a day of work until now, I’ve always given a hundred and ten percent. And meanwhile, I see all these rich white guys (“no offense, doctor,” he added, clearly overestimating the salary of a medical resident) who kind of coast through school, coast into college, end up with 9 – 4 desk jobs working for a friend of their father’s with excellent salaries and benefits, and if they need to miss a couple of days of work, whether it’s for a hospitalization or just to go on a cruise, nobody questions it one way or the other. I’m a harder worker than they are, he said – and I believed him – so how is that fair?

And of course, like most of the people I deal with at my job, there’s no good answer except maybe restructuring society from the ground up, so I gave him some platitudes about how it’s not his fault, told him about all the social services available to him, and gave him a pill to treat a biochemical condition almost completely orthogonal to his real problem.

And I’m still not sure what a good response to his question would have been. But later that night I was browsing the Internet and I was reminded of what the worse response humanly possible. It would go something like:

You keep whining about how “unfair” it is that you can’t get a good job. “But I’m such a hard worker.” No, actual hard workers don’t feel like they’re entitled to other people’s money just because they ask nicely.

“Why do rich white kids who got legacy admissions to Yale receive cushy sinecures, but I have to work two grueling minimum wage jobs just to keep a roof over my head?” By even asking that question, you prove that you think of bosses as giant bags of money, rather than as individual human beings who are allowed to make their own choices. No one “owes” you money just because you say you “work hard”, and by complaining about this you’re proving you’re not really a hard worker at all. I’ve seen a lot of Hard Workers (TM) like you, and scratch their entitled surface and you find someone who thinks just because they punched a time card once everyone needs to bow down and worship them.

If you complain about “rich white kids who get legacy admissions to Yale,” you’re raising a huge red flag that you’re the kind of person who steals from their employer, and companies are exactly right to give you a wide berth.

Such a response would be so antisocial and unjust that it could only possibly come from the social justice movement.

II.

I’ve been thinking about “nice guys” lately for a couple of reasons.

First, I read Alas, A Blog‘s recent post on the subject, MRAs And Anti-Feminists Have Ruined Complaining About Being Single.

Second, I had yet another patient who -

(I feel obligated to say at this point that the specific details of these patient stories are made up, and several of them are composites of multiple different people, in order to protect confidentiality. I’m preserving the general gist, nothing more)

- I had a patient, let’s call him ‘Henry’ for reasons that are to become clear, who came to hospital after being picked up for police for beating up his fifth wife.

So I asked the obvious question: “What happened to your first four wives?”

“Oh,” said the patient, “Domestic violence issues. Two of them left me. One of them I got put in jail, and she’d moved on once I got out. One I just grew tired of.”

“You’ve beaten up all five of your wives?” I asked in disbelief.

“Yeah,” he said, without sounding very apologetic.

“And why, exactly, were you beating your wife this time?” I asked.

“She was yelling at me, because I was cheating on her with one of my exes.”

“With your ex-wife? One of the ones you beat up?”

“Yeah.”

“So you beat up your wife, she left you, you married someone else, and then she came back and had an affair on the side with you?” I asked him.

“Yeah,” said Henry.

I wish, I wish I wish, that Henry was an isolated case. But he’s interesting more for his anomalously high number of victims than for the particular pattern.

Last time I talked about these experiences, one of my commenters linked me to what was later described as the only Theodore Dalrymple piece anyone ever links to. Most of the commenters saw a conservative guy trying to push an ideological point, and I guess that’s part of it. But for me it looked more like the story of a psychiatrist from an upper-middle-class background suddenly realizing how dysfunctional and screwed-up a lot of his patients are and having his mind recoil in horror from the fact – which is something I can sympathize with. Henry was the worst of a bad bunch, but nowhere near unique.

When I was younger – and I mean from teeanger hood all the way until about three years ago – I was a nice guy. In fact, I’m still a nice guy at heart, I just happen to mysteriously have picked up girlfriends. And I said the same thing as every other nice guy, which is “I am a nice guy, how come girls don’t like me?”

There seems to be some confusion about this, so let me explain what it means, to everyone, for all time.

It does not mean “I am nice in some important cosmic sense, therefore I am entitled to sex with whomever I want.”

It means: “I am a nicer guy than Henry.”

Or to spell it out very carefully, Henry clearly has no trouble with women. He has been married five times and had multiple extra-marital affairs and pre-marital partners, many of whom were well aware of his past domestic violence convictions and knew exactly what they were getting into. Meanwhile, here I was, twenty-five years old, never been on a date in my life, every time I ask someone out I get laughed at, I’m constantly teased and mocked for being a virgin and a nerd whom no one could ever love, starting to develop a serious neurosis about it.

And here I was, tried my best never to be mean to anyone, gave to charity, pursuing a productive career, worked hard to help all of my friends. I didn’t think I deserved to have the prettiest girl in school prostrate herself at my feet. But I did think I deserved to not be doing worse than Henry.

No, I didn’t know Henry at the time. But everyone knows a Henry. Most people know several. Even three years ago, I knew there were Henry-like people – your abusers, your rapists, your bullies – and it wasn’t hard to notice that none of them seemed to be having the crushing loneliness problem I was suffering from.

And, like my patient Dan, I just wanted to know – how is this fair?

And I made the horrible mistake of asking this question out loud, and that was how I learned about social justice.

III.

We will now perform an ancient and traditional Slate Star Codex ritual, where I point out something I don’t like about feminism, then everyone tells me in the comments that no feminist would ever do that and it’s a dirty rotten straw man, then I link to two thousand five hundred examples of feminists doing exactly that, then everyone in the comments No-True-Scotsmans me by saying that that doesn’t count and those people aren’t representative of feminists, then I find two thousand five hundred more examples of the most prominent and well-respected feminists around saying exactly the same thing, then my commenters tell me that they don’t count either and the only true feminist lives in the Platonic Realm and expresses herself through patterns of dewdrops on the leaves in autumn and everything she says is unspeakably kind and beautiful and any time I try to make a point about feminism using examples from anyone other than her I am a dirty rotten motivated-arguer trying to weak-man the movement for my personal gain.

Ahem.

From Jezebel, “Why We Should Mock The Nice Guys Of OKCupid”:

Pathetic and infuriating in turns, the profiles selected for inclusion [on a site that searches OKCupid profiles for ones that express sadness at past lack of romantic relationships, then posts them publicly for mockery] elicit gasps and giggles – and they raise questions as well. Is it right to mock these aggrieved and clueless young men, particularly the ones who seem less enraged than sad and bewildered at their utter lack of sexual success?What’s on offer isn’t just an opportunity to snort derisively at the socially awkward; it’s a chance to talk about the very real problem of male sexual entitlement. The great unifying theme of the curated profiles is indignation. These are young men who were told that if they were nice, then, as Laurie Penny puts it, they feel that women “must be obliged to have sex with them.” The subtext of virtually all of their profiles, the mournful and the bilious alike, is that these young men feel cheated. Raised to believe in a perverse social/sexual contract that promised access to women’s bodies in exchange for rote expressions of kindness, these boys have at least begun to learn that there is no Magic Sex Fairy. And while they’re still hopeful enough to put up a dating profile in the first place, the Nice Guys sabotage their chances of ever getting laid with their inability to conceal their own aggrieved self-righteousness.

So how should we respond, when, as Penny writes, “sexist dickwaddery puts photos on the internet and asks to be loved?” The short answer is that a lonely dickwad is still a dickwad; the fact that these guys are in genuine pain makes them more rather than less likely to mistreat the women they encounter.

From XOJane, Get Me Away From Good Guys:

Let’s tackle those good guys. You know, the aw shucks kind who say it’s just so hard getting a date or staying in a relationship, and they can’t imagine why they are single when they are, after all, such catches. They’re sensitive, you know. They totally care about the people around them, would absolutely rescue a drowning puppy if they saw one.

Why is it that so many “good guys” act like adult babies, and not in a fetish sense? They expect everyone else to pick up their slack, they’re inveterately lazy, and they seem genuinely shocked and surprised when people are unimpressed with their shenanigans. Their very heteronormativity betrays a shockingly narrow view of the world; ultimately, everything boils down to them and their needs, by which I mean their penises.

The nice guy, to me, is like the “good guy” leveled up. These are the kinds of people who say that other people just don’t understand them, and the lack of love in their lives is due to other people being shitty. Then they proceed to parade hateful statements, many of which are deeply misogynist, to explain how everyone else is to blame for their failures in life. A woman who has had 14 sexual partners is a slut. These are also the same guys who do things like going into a gym, or a school, or another space heavily populated by women, and opening fire. Because from that simmering sense of innate entitlement comes a feeling of being wronged when he doesn’t get what he wants, and he lives in a society where men are “supposed” to get what they want, and that simmer can boil over.

I’ve noted, too, that this kind of self-labeling comes up a lot in men engaging in grooming behavior. As part of their work to cultivate potential victims, they remind their victims on the regular that they’re “good guys” and the only ones who “truly” understand them.

From Feminspire, Nice Guy Syndrome And The Friend Zone:

I’m pretty sure everyone knows at least one Nice Guy. You know, those guys who think women only want to date assholes and just want be friends with the nice guys. These guys are plagued with what those of us who don’t suck call Nice Guy Syndrome.It’s honestly one of the biggest loads of crap I’ve ever heard. Nice Guys are arrogant, egotistical, selfish douche bags who run around telling the world about how they’re the perfect boyfriend and they’re just so nice. But you know what? If these guys were genuinely nice, they wouldn’t be saying things like “the bitch stuck me in the friend zone because she only likes assholes.” Guess what? If she actually only liked assholes, then she would likely be super attracted to you because you are one.

Honestly. Is it really that unbearable to be friends with a person? Women don’t only exist to date or have sex with you. We are living, thinking creatures who maybe—just maybe—want to date and sex people we’re attracted to. And that doesn’t make any of us bitches. It makes us human.

From feministe, “Nice Guys”:

If a self-styled “Nice Guy” complains that the reason he can’t get laid is that women only like “jerks” who treat them badly, chances are he’s got a sense of entitlement on him the size of the Unisphere.Guys who consider themselves “Nice Guys” tend to see women as an undifferentiated mass rather than as individuals. They also tend to see possession of a woman as a prize or a right…

A Nice Guy™ will insist that he’s doing everything perfectly right, and that women won’t subordinate themselves to him properly because he’s “Too Nice™,” meaning that he believes women deserve cruel treatment and he would like to be the one executing the cruelty.

However, Feministe is the first to show a glimmer of awareness (second, if you count Jezebel’s “I realize this might be construed as mean BUT I LOVE BEING MEAN” as “awareness”):

For the two hundredth time, when we’re talking about “nice guys,” we’re not talking about guys who are actually nice but suffer from shyness. That’s why the scare quotes. Try Nice Guys instead, if you prefer.A shy, but decent and caring man is quite likely to complain that he doesn’t get as much attention from women as he’d like. A Nice Guy™ will complain that women don’t pay him the attention he deserves. The essence of the distinction is that the Nice Guy™ feels women are obligated to him, and the Nice Guy™ doesn’t actually respect or even like women. The clearest indication of which of the two you’re dealing with is whether the person is interested in the possibility that he’s doing something wrong.

Okay. Let’s extend our analogy from above.

It was wrong of me to say I hate poor minorities. I meant I hate Poor Minorities! Poor Minorities is a category I made up that includes only poor minorities who complain about poverty or racism.

No, wait! I can be even more charitable! A poor minority is only a Poor Minority if their compaints about poverty and racism come from a sense of entitlement. Which I get to decide after listening to them for two seconds. And If they don’t realize that they’re doing something wrong, then they’re automatically a Poor Minority.

I dedicate my blog to explaining how Poor Minorities, when they’re complaining about their difficulties with poverty or asking why some people like Paris Hilton seem to have it so easy, really just want to steal your company’s money and probably sexually molest their co-workers. And I’m not being unfair at all! Right? Because of my new definition! I know everyone I’m talking to can hear those Capital Letters. And there’s no chance whatsoever anyone will accidentally misclassify any particular poor minority as a Poor Minority. That’s crazy talk! I’m sure the “make fun of Poor Minorities” community will be diligently self-policing against that sort of thing. Because if anyone is known for their rigorous application of epistemic charity, it is the make-fun-of-Poor-Minorities community!

I’m not even sure I can dignify this with the term “motte-and-bailey fallacy”. It is a tiny Playmobil motte on a bailey the size of Russia.

I don’t think I ever claimed to be, or felt, entitled to anything. Just wanted to know why it was that people like Henry could get five wives and I couldn’t get a single date. That was more than enough to get the “shut up you entitled rapist shitlord” cannon turned against me, with the person who was supposed to show up to give me the battery of tests to distinguish whether I was a poor minority or a Poor Minority nowhere to be seen. As a result I spent large portions of my teenage life traumatized and terrified and self-loathing and alone.

Some recent adorable Tumblr posts (1, 2) pointed out that not everyone who talks about social justice is a social justice warrior. There are also “social justice clerics, social justice rogues, social justice rangers, and social justice wizards”. Fair enough.

But there are also social justice chaotic evil undead lich necromancers.

And the people who talk about “Nice Guys” – and the people who enable them, praise them, and link to them – are blurring the already rather thin line between “feminism” and “literally Voldemort”.

IV.

And so we come to Barry’s recent blog post:

In pop culture, everyone – or at least, everyone who isn’t a terrible human being – eventually meets someone wonderful and falls in love.But in real life, that’s not how things always work. Some people don’t want romantic love at all. Others want romantic love but will never find it. That’s life. I’m beginning to accept, at age 45, that probably “true love” will never happen for me. I have a bunch of factors working against me – I’m physically conventionally unattractive, I badly lack confidence, I’m sort of a weirdo, as I get older I meet new people less often, etc..

To tell you the truth, I resent the situation. It’s not an all-consuming bitterness or anything – on the whole, I’m a happy guy – but I irrationally feel cheated of a fundamental human experience…

I bring this up because I feel my ability to enjoy complaining about my single state has been ruined by MRAs and anti-feminists.

Because in human culture, we do something called “signaling” a lot. And, on the internet, men complaining that they don’t have the romantic success they want, that they feel they should be more attractive to woman then they actually are in practice, etc., have all become signals used to indicate alliance with the manosphere.

Gore Vidal once groused that the once-useful word “turgid” now belongs to the porn writers, because it has become impossible to use the word without sounding like a porn writer. The manosphere has done something similar to unattractive men’s romantic problems. They’ve flooded the discourse with misogyny and anti-feminism, and it’s nearly impossible to rescue discussion of being male and unwanted from their bitter waters.

Let me start by saying I sympathize with Barry, as someone who has been in exactly his position. And that if anyone uses this post as an excuse to attack Barry personally, they are going to Hell and getting banned from SSC. They’re also proving the point of whichever side they are not on.

What I don’t sympathize with is Barry’s belief that this is somehow the fault of “the manosphere” “flooding the discourse”.

It would actually be pretty fun to go full internet-archaeologist on the manosphere, but a quick look confirms my impression that, although it is built from older pieces, it’s really quite young. There was a “men’s rights” movement around forever, but its early focus tended to be on divorce cases and fathers’ rights. Heartiste started publishing in 2007. The word “manosphere” was first used in late 2009. Google Trends confirms a lot of this.

So I think it’s fair to attribute low to minimal influence for Manosphere-type stuff before about 2005 at the earliest.

But feminists were complaining about “nice guys” for much longer. According to Wikipedia, the concept dates at least from a 2002 article called Why “Nice Guys” are often such LOSERS, which was billed as a “Bitchtorial” on feminist blog “Heartless Bitches International”

(Once again, I swear I don’t make up the names of these feminist blogs as some sort of strawmanning strategy. They just happen like that!)

Looking into “Heartless Bitches Internation”, its header image is the words “Nice Guys = Bleah!” and its blog tagline is “What’s wrong with Nice Guys? HBI Tells It Like It Is”. This was seven years before the term “manosphere” even existed.

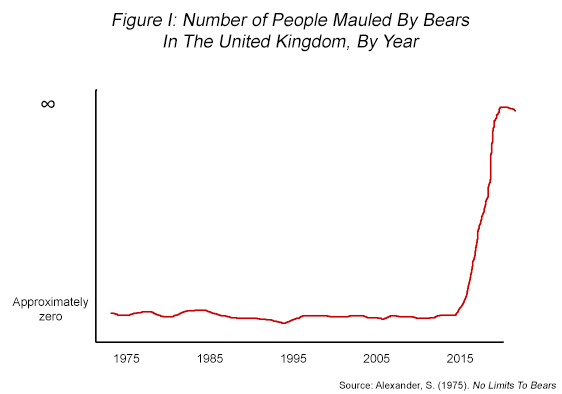

I can’t Google Trends “Nice Guys”, because it picks up too much interference from normal discussion of people who are nice. But there is one more Google Trends graph that I think relates to this issue:

This is the same graph as before. You can’t tell, because I’ve added the word “feminism”, which has caused every other line on the graph to shrink into invisibility. The purple line is – what, twenty, thirty times as high as any of the others?

People were coming up with reasons to mock and despise men who were sad about not being in relationships years before the manosphere even existed. These reasons were being posted on top feminist blogs for years without any reference whatsoever to the manosphere, probably because the people who wrote them were unaware of its existence or couldn’t imagine what it could possibly have to do with this subject? Feminism – the movement that was doing all this with no help from the manosphere – has twenty times the eyeballs and twenty times the discourse-setting power as the manosphere. And Barry thinks this is the manosphere’s fault? On the SSC “Things Feminists Should Not Be Able To Get Away With Blaming On The Manosphere” Scale, this is right up there with the postulated link between the men’s rights movement and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

The worst corners of the manosphere contain more than enough opining on how ugly women, weird women, masculine women, et cetera deserve to be unhappy. You are welcome to read, for example, Matt Forney’s Why Fat Women Don’t Deserve To Be Loved (part of me feels like the link is self-trigger-warning, but I guess I will just warn you that this is not a clever attention-grabbing title, the link means exactly what it says and argues it at some length)

I am not the first person to notice that the feminist blogosphere and the manosphere are in many ways mirror images of each other. Some feminists give incisive criticism of social structures that affect women; some manospherites give incisive criticism of social structures that affect men. On the other hand, some feminists are evil raving loonies and some manospherites are evil raving loonies. Feminists talk about male privilege and misogyny, manospherites talk about female privilege and misandry. Some people try to deny the symmetry, but that usually says more about what they pay attention to than it does the underlying territory.

No one says the only reason manospherites like to insult unattractive lonely women is because “it’s hard for women to complain about how they’re single without being mistaken for a feminist”, or that “the manosphere doesn’t mean all lonely women, it’s just talking about how offended they are that lonely women feel entitled to sex and objectify men”. In the case of men, everyone pretty much agrees that no, if you’re a certain kind of person, making fun of people for being unattractive and unhappy is its own reward.

The idea of deep genetic and personality differences between men and women is far too complicated to get into here, but I will say that if differences exist, I do not believe they are so great as to change fundamental human nature. For women just as well as men, for feminists just as well as manospherites, if you’re a certain kind of person, making fun of people for being unattractive and unhappy is its own reward. Hence everything that has ever been said about “nice guys (TM)”

The only difference between the feminists and the manosphere here is that people call out the manosphere when they do it. But the feminists have their little Playmobil motte, so that’s totally different!

V.

So am I claiming that the feminist war on “nice guys” is totally uncorrelated with the existence of the manosphere?

No. I’m saying the causal arrow goes the opposite direction from the one Barry’s suggesting. As usual with gender issues, this can be best explained through a story from ancient Chinese military history.

Chen Sheng was an officer serving the Qin Dynasty, famous for their draconian punishments. He was supposed to lead his army to a rendezvous point, but he got delayed by heavy rains and it became clear he was going to arrive late. The way I always hear the story told is this:

Chen turns to his friend Wu Guang and asks “What’s the penalty for being late?”

“Death,” says Wu.

“And what’s the penalty for rebellion?”

“Death,” says Wu.

“Well then…” says Chen Sheng.

And thus began the famous Dazexiang Uprising, which caused thousands of deaths and helped usher in a period of instability and chaos that resulted in the fall of the Qin Dynasty three years later.

The moral of the story is that if you are maximally mean to innocent people, then eventually bad things will happen to you. First, because you have no room to punish people any more for actually hurting you. Second, because people will figure if they’re doomed anyway, they can at least get the consolation of feeling like they’re doing you some damage on their way down.

This seems to me to be the position that lonely men are in online. People will tell them they’re evil misogynist rapists – as the articles above did – no matter what. In what is apparently shocking news to a lot of people, this makes them hurt and angry. As someone currently working on learning psychotherapy, I can confidently say that receiving a constant stream of hatred and put-downs throughout your most formative years can really screw you up. And so these people try to lash out at the people who are doing it to them, secure in the knowledge that there’s no room left for people to hate them even more.

I know this is true because it happened to me. I never became a manospherian per se, because two wrongs don’t make a right, but – as readers of this essay may be surprised to learn – I did become just a little bit bitter about feminism. If I hadn’t been so sure about that “two wrongs” issue I probably would have ended up a lot more radicalized.

Actually, that word – “radicalized” – conceals what is basically my exact thesis. We talk a lot about the “radicalization” of Muslims – for example, in Palestine. And indeed, nobody likes Hamas and we all agree they are terrible people and commit some terrible atrocities. Humans can certainly be very cruel, but there seems to be an unusual amount of cruelty in this particular region. And many people who like black-and-white thinking try to blame that on some defect in the Palestinian race, or claim the Quran urges Muslims should be hateful and violent. But if you’re willing to tolerate a little bit more complexity, it may occur to you to ask “Hey, I wonder if any of this anger among Palestinians has to do with the actions of Israel?” And then you might notice, for example, the past century of Middle Eastern history.

Yet somehow, when the manosphere is being terrible people and commiting terrible atrocities, the only explanation offered is that “you must hate all women” must appear in some sura of the Male Quran.

My patient – not Henry, the one I started this whole thing off with, the one who works two minimum wage jobs and wants to know why he’s still falling behind when everyone else does so well – he wasn’t listed as a danger to himself or others, so he had the right to leave the hospital voluntarily if he wanted to. And he did, less than two days after he came in, before we’d even managed to finalize a treatment plan for him. He was worried that his boss was going to fire him if he stayed in longer.

I didn’t get a chance to give him any medication – not that it would have helped that much. All I got a chance to do was to tell him I respected his situation, that he was in a really sucky position, that it wasn’t his fault, and that I hoped he did better. I’m sure my saying that had minimal effect on him. But maybe a history of getting to hear that message from all different people – friends, family, doctors, social workers, TV, church, whatever – all through his life – gave him enough mental fortitude to go back to his horrible jobs and keep working away in the hopes that things would get better. Instead of killing himself or turning to a life of crime or joining the latest kill-the-rich demagogue movement or whatever.

In the end what he wanted wasn’t entitlement to other people’s money, or a pity job from someone who secretly didn’t like him. All he needed to keep going was to have people acknowledge there was a problem and treat him like a frickin’ human being.

VI.

So let’s get back to Barry.

(remember, anyone who uses this article to insult Barry will go to Hell and get banned from Slate Star Codex)

Barry is using my second-favorite rhetorical device, apophasis, the practice of bringing up something by denying that it will be brought up. For example, “I think the American people deserve a clean debate, and that’s why I’m going to stick to the issues, rather than talking about the incident last April when my opponent was caught having sex with a goat. Anyway, let’s start with the tax rate…”

He is complaining about being single by saying that you can’t complain about being single – and, as a bonus, placating feminists by blaming the whole thing on the manosphere as a signal that he’s part of their tribe and so should not be hurt.

It almost worked. He only got one comment saying he was privileged and entitled (which he dismisses as hopefully a troll). But he did get some other comments that remind me of two of my other least favorite responses to “nice guys”.

First: “Nice guys don’t want love! They just want sex!”

One line disproof: if they wanted sex, they’d give a prostitute a couple bucks instead of spiralling into a giant depression.

Second: “You can’t compare this to, like, poor people who complain about being poor. Food and stuff are basic biological human needs! Sex isn’t essential for life! It’s an extra, like having a yacht, or a pet tiger!”

I know that feminists are not always the biggest fans of evolutionary psychology. But I feel like it takes a special level of unfamiliarity with the discipline to ask “Sure, evolution gave us an innate desire for material goods, but why would it give us an deep innate desire for pair-bonding and reproduction??!”

But maybe a less sarcastic response would be to point out Harry Harlow’s monkey studies. These studies – many of them so spectacularly unethical that they helped kickstart the modern lab-animals’-rights movement – included one in which monkeys were separated from their real mother and given a choice between two artifical “mothers” – a monkey-shaped piece of wire that provided milk but was cold and hard to the touch, and a soft cuddly cloth mother that provided no milk. The monkeys ended up “attaching” to the cloth mother and not the milk mother.

In other words – words that shouldn’t be surprising to anyone who has spent much time in a human body – companionship and warmth can be in some situations just as important as food and getting your more basic needs met. Friendship can meet some of that need, but for a lot of people it’s just not enough.

When your position commits you to saying “Love isn’t important to humans and we should demand people stop caring about whether or not they have it,” you need to take a really careful look in the mirror – assuming you even show up in one.

VII.

You’re seven sections in, and maybe you thought you were going to get through an entire SSC post without a bunch of statistics. Ha ha ha ha ha.

I will have to use virginity statistics as a proxy for the harder-to-measure romancelessness statistics, but these are bad enough. In high school each extra IQ point above average increases chances of male virginity by about 3%. 35% of MIT grad students have never had sex, compared to only 13% of the average high school population. Compared with virgins, men with more sexual experience are likely to drink more alcohol, attend church less, and have a criminal history. A Dr. Beaver (nominative determinism again!) was able to predict number of sexual partners pretty well using a scale with such delightful items as “have you been in a gang”, “have you used a weapon in a fight”, et cetera. An analysis of the psychometric Big Five consistently find that high levels of disagreeableness predict high sexual success in both men and women.

If you’re smart, don’t drink much, stay out of fights, display a friendly personality, and have no criminal history – then you are the population most at risk of being miserable and alone. “At risk” doesn’t mean “for sure”, any more than every single smoker gets lung cancer and every single nonsmoker lives to a ripe old age – but your odds get worse. In other words, everything that “nice guys” complain of is pretty darned accurate. But that shouldn’t be too hard to guess…

Sorry. We were talking about Barry.

I have said no insulting Barry, but I never banned complimenting him. Barry is a neat guy. He draws amazing comics and he runs one of the most popular, most intellectual, and longest-standing feminist blogs on the Internet. I have debated him several times, and although he can be enragingly persistent he has always been reasonable and never once called me a neckbeard or a dudebro or a piece of scum or anything. He cares deeply about a lot of things, works hard for those things, and has supported my friends when they have most needed support.

If there is any man in the world whose feminist credentials are impeccable, it is he. And I say this not to flatter him, but to condemn everyone who gives the nice pat explanation “The real reason Nice Guys™®© can’t get dates is that women can just tell they’re misogynist, and if they were to realize women were people then they would be in relationships just as much as anyone else.” This advice I see all the time, most recently on a feminist “dating advice for single guys” list passed around on Facebook:

Step I. Consume More Art By Women – I think it’s a good idea to make a deliberate year-long project of it at this time in your life, when you are trying to figure out how to relate to women better…Use woman-created media to to remind yourself that the world isn’t only about you + men + women who have/have not rejected you as a romantic partner.

I want to reject that line of thinking for all time. I want to actually go into basic, object-level Nice Guy territory and say there is something very wrong here.

Barry is possibly the most feminist man who has ever existed, palpably exudes respect for women, and this is well-known in every circle feminists frequent. He is reduced to apophatic complaints about how sad he is that he doesn’t think he’ll ever have a real romantic relationship.

Henry has four domestic violence charges against him by his four ex-wives and is cheating on his current wife with one of those ex-wives. And as soon as he gets out of the psychiatric hospital where he was committed for violent behavior against women and maybe serves the jail sentence he has pending for said behavior, he is going to find another girlfriend approximately instantaneously.

And this seems unfair. I don’t know how to put the basic insight behind niceguyhood any clearer than that. There are a lot of statistics backing up the point, but the statistics only corroborate the obvious intuitive insight that this seems unfair.

And suppose, in the depths of your Forever Alone misery, you make the mistake of asking why things are so unfair.

Well, then Jezebel says you are “a lonely dickwad who believes in a perverse social/sexual contract that promises access to women’s bodies”. XOJane says you are “an adult baby” who will “go into a school or a gym or another space heavily populated by women and open fire”. Feminspire just says you are “an arrogant, egotistical, selfish douche bag”.

And the manosphere says: “Excellent question, we’ve actually been wondering that ourselves, why don’t you come over here and sit down with us and hear some of our convincing-sounding answers, which, incidentally, will also help solve your personal problems?”

And feminists still insist the only reason anyone ever joins the manosphere is “distress of the privileged”!

I do not think men should be entitled to sex, I do not think women should be “blamed” for men not having sex, I do not think anyone owes sex to anyone else, I do not think women are idiots who don’t know what’s good for them, I do not think anybody has the right to take it into their own hands to “correct” this unsettling trend singlehandedly.

But when you deny everything and abuse anyone who brings it up, you cede this issue to people who sometimes do think all of these things. And then you have no right to be surprised when all the most frequently offered answers are super toxic.

There is a very simple reply to the question which is better than anything feminists are now doing. It is the answer I gave to my patient Dan: “Yeah, things are unfair. I can’t do anything about it, but I’m sorry for your pain. Here is a list of resources that might be able to help you.”

There is also a more complicated reply, which I am not qualified to compose, but I think the gist of it would be something like:

Personal virtue is not very well correlated with ease of finding a soulmate. It may be only slightly correlated, uncorrelated, or even anti-correlated in different situations. Even smart people who want various virtues in a soulmate usually use them as a rule-out criterion, rather than a rule-in criterion – that is, given someone whom they are already attracted to, they will eliminate him if he does not have those virtues. The rule-in criterion that makes you attractive to people is mysterious and mostly orthogonal to virtue. This is true both in men and women, but in different ways. Male attractiveness seems to depend on things like a kind of social skills which is not necessarily the same kind of social skills people who want to teach you social skills will teach, testosterone level, social status, and whatever you call the ability to just ask someone out, consequences be damned. These can be obtained in very many different ways that are partly within your control, but they are complicated and subtle and if you naively aim for cliched versions of the terms you will fail. There is a lot of good discussion about how to get these things. Here is a list of resources that might be able to help you.

Of course, then you’ve got to have your resource list. And – and this is the part of this post I think will be controversial (!), I think a lot of the appropriate material is concentrated in the manosphere, ie the people who do not hate your guts merely for acknowledging the existence of the issue. Yes, it is interspersed with poisonous beliefs about women being terrible, but if you have more than a quarter or so of a soul, it is pretty easy to filter those out and concentrate on the good ones. Many feminists will say there are no good ones and that they are all exactly the same, but you should not believe them for approximately the same reason you should not believe anyone else who claims the outgroup is completely homogenous and uniformly evil. Ozy has tried to pick out some of the better ones for you at the bottom of their their anti-Heartiste FAQ, and a guy called John on Tumblr has added to the discussion.

So I think the better parts of feminism and the better parts of the manosphere could unite around something like this, against the evil fringes of both movements. Not for my sake, because after many years I mysteriously and unexpectedly found a wonderful girlfriend whom I love very much. And not only for the sake of the nice guys out there. But also for the sake of women who want better alternatives to marrying someone like Henry.

And although Barry explicitly doesn’t want dating advice, I feel like this is meta-level enough that it doesn’t count. Stop blaming the men’s movement for the problem and notice the more fundamental problem that some parts of the men’s movement – as well as some parts of feminism are honestly trying to work on.

Come to the Not-Actually-Dark-But-Spends-Slightly-Less-Time-Loudly-Protesting-Its-Lightness Side, Barry. We have cookies! And basic human decency! But also cookies!

. To be honest, I wasn’t really even able to understand Quantum Computing Since Democritus. I knew I was in for trouble when it compared itself to The Elegant Universe in the foreword, since I wasn’t able to get through more than a few chapters of that one. I dutifully tried to do the first couple of math problems Democritus set for me, and I even got a couple of them right. But eventually I realized that if I wanted to read Democritus the way it was supposed to be read, with full or even decent understanding, it would be a multi-year project, a page a day or worse, with my gains fading away a few days after I made them into a cloud of similar-looking formulae and three-letter abbreviations.

. To be honest, I wasn’t really even able to understand Quantum Computing Since Democritus. I knew I was in for trouble when it compared itself to The Elegant Universe in the foreword, since I wasn’t able to get through more than a few chapters of that one. I dutifully tried to do the first couple of math problems Democritus set for me, and I even got a couple of them right. But eventually I realized that if I wanted to read Democritus the way it was supposed to be read, with full or even decent understanding, it would be a multi-year project, a page a day or worse, with my gains fading away a few days after I made them into a cloud of similar-looking formulae and three-letter abbreviations. , which predicted our civilisation would probably collapse some time this century, has been criticised as doomsday fantasy since it was published. Back in 2002, self-styled environmental expert Bjorn Lomborg consigned it to the “dustbin of history”.

, which predicted our civilisation would probably collapse some time this century, has been criticised as doomsday fantasy since it was published. Back in 2002, self-styled environmental expert Bjorn Lomborg consigned it to the “dustbin of history”.

. .

. .

, and one of its best features is its focus on Marx’s influence from Hegel. Hegel is really interesting.

, and one of its best features is its focus on Marx’s influence from Hegel. Hegel is really interesting. The Phenomenology of Spirit —widely considered to be Hegel’s masterpiece—and what do you have to show for it? The book is supposed to take you from the naïve, “immediate” position of “sense certainty” to Absolute Knowledge, “or Spirit that knows itself as Spirit.” That sounds pretty good, especially when you are, say, eighteen and are busy soaking up ideas guaranteed to mystify and alarm your parents. But what do you suppose it means?

The Phenomenology of Spirit —widely considered to be Hegel’s masterpiece—and what do you have to show for it? The book is supposed to take you from the naïve, “immediate” position of “sense certainty” to Absolute Knowledge, “or Spirit that knows itself as Spirit.” That sounds pretty good, especially when you are, say, eighteen and are busy soaking up ideas guaranteed to mystify and alarm your parents. But what do you suppose it means? and has been gradually releasing faction information. They have a tough job: they need to live up to the beloved factions of their predecessors, match them to real-world countries, have them be sufficiently different to be interesting, and avoid the trap where there is the Generic Military Faction which thinks Strength Is The Greatest Good and the Generic Religious Faction which wants to Kill The Infidel. Currently I rate them a “C”. The

and has been gradually releasing faction information. They have a tough job: they need to live up to the beloved factions of their predecessors, match them to real-world countries, have them be sufficiently different to be interesting, and avoid the trap where there is the Generic Military Faction which thinks Strength Is The Greatest Good and the Generic Religious Faction which wants to Kill The Infidel. Currently I rate them a “C”. The

because my biggest gripe after reading

because my biggest gripe after reading  makes the bold claim that most differences in how parents bring up their children don’t really change the children’s long-term outcomes that much. This obviously contradicts a wide body of research, and she goes at length into why she thinks the wide body of research is wrong.

makes the bold claim that most differences in how parents bring up their children don’t really change the children’s long-term outcomes that much. This obviously contradicts a wide body of research, and she goes at length into why she thinks the wide body of research is wrong. :

: